This article contains discussion of mental health and the Holocaust.

Dr. Edith Eger lived through one of the most horrific events of the 20th century. When she was 16 years old, her entire family was taken to the infamous death camp, Auschwitz. Her mother was killed immediately, and she endured unimaginable trauma at the hands of the Nazis for nearly a year.

Dr. Eger was one of the few left alive when Auschwitz was liberated in 1945, and though the physical terrors of the camp were over, the emotional terrors remained. She struggled with nightmares and flashbacks, but she didn’t know how to talk about what she’d been through — so she continued to live in the trauma.

It took her years of pain to discover that trying to minimize or hide from her horrible experiences prevented her from healing. When she was finally ready, Dr. Eger looked at what happened to her honestly, shared her story with others, and started to reshape the way she thought about it.

Now, she is a clinical psychologist who helps people break free from the “mental prisons” created by trauma. In an exclusive interview with Health Digest, Dr. Eger talked about how she’s recovering from the trauma of her past, how she helps others heal, and how she created her new online course for anyone who wants to break free of whatever’s holding them back.

Living through ‘hell’

Can you tell us a little bit about your life and what the trauma you’ve been through has taught you about life?

In the spring of 1944, I was 16, living with my parents and two older sisters in Kassa, Hungary. There were signs of war and prejudice all around us — the yellow stars we wore pinned to our coats. Then they came in the night, and after a long ordeal, we ended up at the death camp Auschwitz. Immediately, my mother was taken from me and killed in the gas chamber.

While there, I was forced to dance for SS officer Josef Mengele, known as the Angel of Death. This was the man who had scrutinized the new arrivals as we came through the gate of Auschwitz that day and sent my mother to her death. “Dance for me!” he ordered, and I stood on the cold concrete floor of the barracks, frozen with fear. Outside, the camp orchestra began to play a waltz, “The Blue Danube.”

Remembering my mother’s advice — “No one can take from you what you’ve put in your mind” — I closed my eyes and retreated to an inner world. In my mind, I was no longer imprisoned in a death camp, cold and hungry and ruptured by loss. Instead, I embodied what gave me inner strength, being a ballerina. I imagined I was on the stage of the Budapest opera house, dancing the role of Juliet in Tchaikovsky’s ballet. From within this private refuge, I willed my arms to lift and my legs to twirl. I summoned the strength to dance for my life.

Each moment in Auschwitz was hell on earth. It was also my best classroom. Subjected to loss, torture, starvation, and the constant threat of death, I discovered the tools for survival and freedom that I continue to use every day in my clinical psychology practice as well as in my own life.

As a psychologist; as a mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother; as an observer of my own and others’ behavior; and as an Auschwitz survivor, I am here to tell you that the worst prison is not the one the Nazis put me in. The worst prison is the one I built for myself in my mind.

Although our lives have probably been very different, perhaps you know what I mean. Many of us experience feeling trapped in our minds. Our thoughts and beliefs determine — and often limit — how we feel, what we do, and what we think is possible. In my work, I’ve discovered that while our imprisoning beliefs show up and play out in unique ways, there are some common mental prisons that contribute to suffering. I have dedicated my life to helping others escape this mental prison by realizing that the key is already in their pocket.

Starting to heal

Can you tell us a bit — whatever you’re willing to share — about your struggles with mental health, particularly post-traumatic stress? How did you start your healing journey?

Three-quarters of a century after liberation, I still have nightmares. I suffer flashbacks. Till the day I die, I will grieve the loss of my parents, who never got to see four generations rise from the ashes of their deaths. The horror is still with me. There’s no freedom in minimizing what happened, or in trying to forget.

But remembering and honoring are very different from remaining stuck in guilt, shame, anger, resentment, or fear about the past. I can face the reality of what happened and remember that although I have lost, I’ve never stopped choosing love and hope. For me, the ability to choose, even in the midst of so much suffering and powerlessness, is the true gift that came out of my time in Auschwitz.

Why did you decide to study psychology?

I don’t want people to read my story and think, “There’s no way my suffering compares to hers.” I want people to hear my story and think, “If she can do it, so can I!” I studied psychology to inspire my patients to start on their journey of recovery.

I’d been teaching at a high school in El Paso for a few years — and had even been awarded teacher of the year — when I decided to return to school for a master’s in educational psychology. One day, my clinical supervisor came to me and said, “Edie, you’ve got to get a doctorate.”

I laughed. “By the time I get a doctorate, I’ll be fifty,” I said. “You’ll be fifty anyway,” he reminded me.

Those are the smartest four words anyone ever said to me. Honey, you’re going to be fifty anyway — or thirty or sixty or ninety — so you might as well take a risk. Do something you’ve never done before. Change is synonymous with growth. To grow, you’ve got to evolve instead of revolve. As I have gone down this path myself, I have learned and grown, and it fills my heart to be able to share these insights and pathways to inner freedom with others.

In America, the slang term for a psychologist is “shrink.” But I like to call myself a stretch!

Unlocking your potential

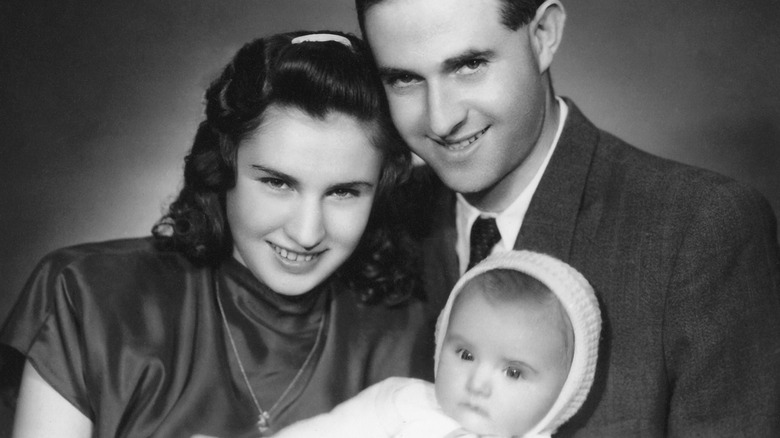

Paul Barnett Photography

Your first online course, Unlocking Your Potential, is launching soon. Congratulations! What can people expect from the course?

I created this course to meet survivor to survivor and guide you to release your self-limiting beliefs and embrace your potential. I realized that though my practice is helping heal individuals, with all the suffering and fear going on in people’s lives today, I needed to do more to bring these teachings to as many people as will benefit from them.

Enjoying the fullness of life may seem like a great goal, but the pathway there is not always clear. Oftentimes, unresolved relationships with our past can spring out at unexpected and seemingly unrelated times, and be in the way of me living with love, purpose, and meaning.

Through 10 modules, I help guide people through uncovering the source of unwanted feelings and behaviors that are in the way of them being the person they were born to be — free. I am so grateful to be joined by my grandson as we go deep into our lives and provide the participants with practices I’ve been curating throughout my career as a psychologist. I love that the course gives people the practical, direct experience for reframing their past and unlocking their potential. The journey to healing can be long and circuitous, and I want to help people get going or go deeper on that journey, to find the strength, peace, and joy inside themselves.

How can the course help people break free from their own mental prisons?

We have to go through the grief work to find forgiveness — for ourselves, for our family, for those that have harmed us. By acknowledging the pain and suffering and then finding ways to also see the gifts that have emerged in me because of my past can I begin to find inner peace. Freedom comes with responsibility. To be responsible for our lives, to take a risk to step out of our mental prisons.

To do this, we gently guide people in the course to explore their memories, their feelings, and their hopes to discover who they truly are and to find the strength to step into that life. It takes practice and time. Self-love is self-care, it is not narcissistic, and I hope that my course can help you discover that peace and love within yourself.

Healing and finding joy again

Jordan Engle

What advice do you have for people struggling with post-traumatic stress, grief, or survivor’s guilt?

Freedom is a lifetime practice — a choice we get to make again and again each day. Ultimately, freedom requires hope, which I define in two ways: the awareness that suffering, however terrible, is temporary; and the curiosity to discover what happens next. Hope allows us to live in the present instead of the past, with our focus on the future we want for ourselves and our families. In this way, we can unlock the doors of our mental prisons.

We all have this capacity to choose. When nothing helpful or nourishing is coming from the outside, that is precisely the moment when we have the possibility to discover who we really are by looking inward. It’s not what happens to us that matters most, it’s what we do with our experiences.

How can people struggling with these issues start to find joy and fulfillment again?

The first steps are to find new perspectives and new relationships with our past. We cannot change our past, but we can change how we think about it. When we can start to remember and rediscover that strength, peace, and wisdom are already within us, we can develop a newer, healthier relationship with ourselves. By reframing our thinking and our language, we create new opportunities to find joy and fulfillment in the little things and the big things.

I am about to turn 95 and have been doing my own inner work for many decades, and still I can get stuck or struggle. Yet I find the moments of inner pain have become less and less, and the opportunities to acknowledge the gifts and feel the joy I have become more and more. It is not someday that I’m “gonna” bring healing to myself. I have already chosen to be free, and in that place, I take each day as it comes. I hope that by listening to my story and [the] practices that I’ve learned, people can begin to find that for themselves.

You can sign up for Dr. Eger’s course here, and for the latest news and resources, please follow Dr. Eger’s Instagram.

This interview was edited for clarity.